Millay at Steepletop

by Holly Peppe

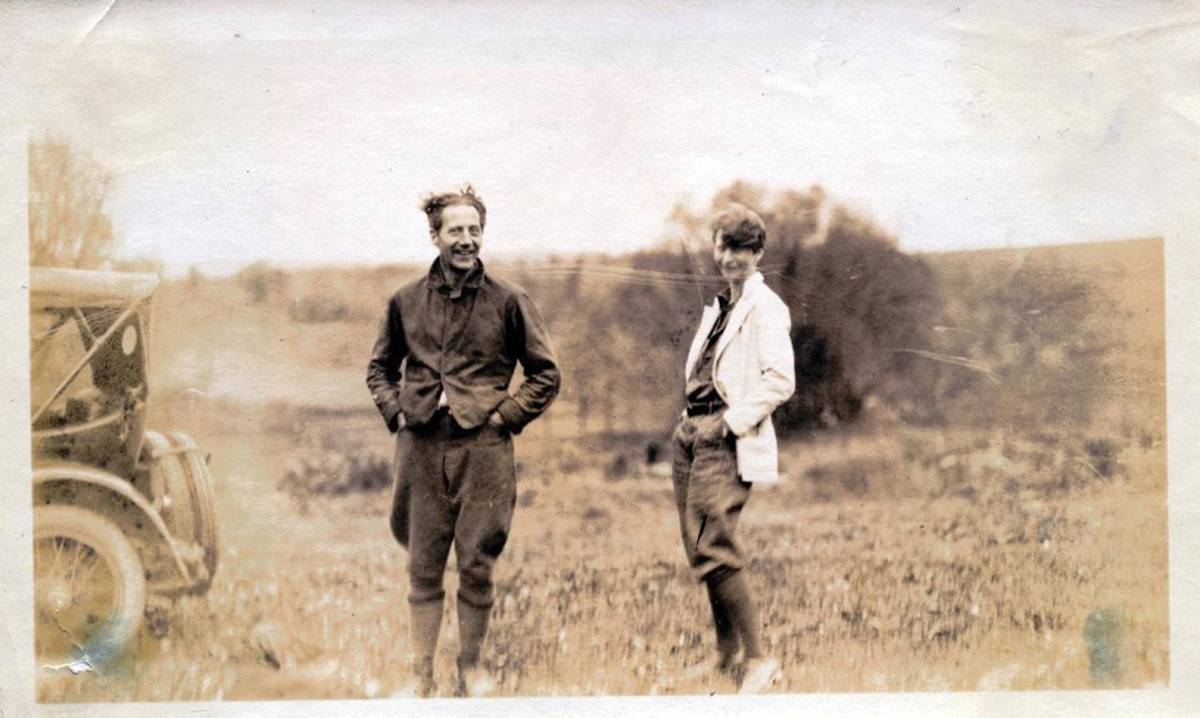

In March 1925, Edna St. Vincent Millay answered an ad in the New York Times for an abandoned berry farm on a hilltop in Austerlitz, New York, a few hours’ drive north of Manhattan. The price tag on 435 acres, a farmhouse, and various barns and outbuildings was $9,000. Anxious to move out of the city, Millay and her husband, Dutch-born coffee importer Eugen Boissevain, moved quickly to secure the deal and soon purchased another 300 acres as well. “I cannot write in New York,” Millay told a reporter. “It is awfully exciting there and I find lots of things to write about and I accumulate many ideas, but I have to go away where it is quiet.” 1

Millay named their new home “Steepletop” after the pink-flowered steeplebush that grew wild in the fields and meadows there. “It’s going to be a sweet place when it’s finished,” she wrote to her mother, “and it’s ours, all ours, about seven hundred acres of land & a lovely house, & no rent to pay, only a nice gentlemanly mortgage to keep shaving a slice off.” 2

Millay’s desire for quiet may have surprised the thousands of devoted readers who considered the bestselling poet a free spirit who belonged to New York’s Greenwich Village, forever living the bohemian life touted in her iconic four-line quatrain:

My candle burns at both ends;

it will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

For the disillusioned post-war youth who claimed her as their spokesperson for women’s rights and social equality, Millay represented the rebellious spirit of their generation. Indeed, though she favored traditional poetic forms like lyrics and sonnets, she boldly reversed conventional gender roles in poetry by empowering the female lover instead of her male suitor, and set a new, shocking precedent by acknowledging female sexuality as a viable literary subject:

I, being born a woman and distressed

By all the needs and notions of my kind,

Am urged by your propinquity to find

Your person fair, and feel a certain zest

To bear your body’s weight upon my breast:

. . .I shall remember you with love, or season

My scorn with pity, let me make it plain:

I find this frenzy insufficient reason

For conversation when we meet again.

When Millay moved to Steepletop, she was 33 and one of the most famous poets in America—her national reading tours sold out weeks in advance. Her unlikely rise to fame started with the publication of a long poem, “Renascence,” when she was just 20. She had entered the poem—107 rhyming couplets describing a life-altering spiritual awakening—in a poetry contest under the name “E. Vincent Millay” to hide her gender. It didn’t win, but when it appeared in The Lyric Year anthology in 1912, readers and critics alike considered it the best poem in the book, and all assumed the author was both older and male. In a note to the editor, another poet in the anthology, Arthur Ficke (who would become her lifelong friend) surmised, “No sweet young thing of 20 ever ended a poem where this one ends: it takes a brawny male of forty-five to do that.”3

As Millay herself responded, “I simply will not be a ‘brawny male’ . . . I cling to my femininity!” 4 Instead she was the eldest of three daughters raised by a single mother, Cora Buzzell Millay, who supported the family by working as a private duty nurse near their home in Camden, on the coast of Maine. Having divorced her husband in 1900, when Millay was eight, Norma six, and Kathleen three, Cora struggled to make ends meet but provided the girls with a steady diet of poetry, literature, and music and encouraged them, by example, to write poems, stories, and songs.

Edna—called Vincent by family and friends—was a talented, spirited, at times overly dramatic adolescent who loved being outdoors: she spent hours alone by the sea and in the garden with her mother, who taught her the names of flowers, plants, and medicinal herbs. In a breathless hymn to nature, she wrote, “Oh world! I cannot hold thee close enough!” Even as a girl she was a prolific writer, winning top poetry prizes in the popular St. Nicholas magazine for young readers. In high school she continued to write poems and songs, starred in school productions, and became editor-in-chief of the school literary magazine.

She graduated in 1909 but, with no financial support, she stayed home to care for her sisters until 1912, when she recited “Renascence” to guests at a local inn where Norma was working, and a woman in the audience, recognizing her talent, offered to help her go to college. Millay was thrilled and decided on Vassar.5 After taking preparatory courses at Barnard in Manhattan, she attended Vassar from 1913-1917, where she honed her acting skills in plays and pageants, some of which she composed herself. She loved studying the classics but disliked the rules: “They trust us with everything but men,” she wrote to Ficke. Just before graduation, though she was caught off campus and told she could not graduate with her class, the college president reversed the decision at the last minute, saying he didn’t want “any dead Shelley’s on [his] doorstep.”6

After graduation, Millay moved to Greenwich Village and enjoyed the bohemian lifestyle of the day. Soon joined by Norma, she published poems in popular magazines like Vanity Fair, Ainslee’s, and the Forum, and poetry collections in salvos and slim leather volumes coveted by an expanding readership. To augment her income she published short stories and satirical sketches under the pen name Nancy Boyd. Both she and Norma also acted with the Provincetown Players and in 1919, she directed her own anti-war play, Aria da Capo, which earned rave reviews.

Millay attracted an attentive coterie of lovers from among the male literati of the day—Floyd Dell, John Peale Bishop, Edmund Wilson, and Witter Bynner—but refused to commit herself to anyone or anything except her work. In 1921, tired of their attentions and wanting to give her poetry “new grass to feed on,” she sailed to Europe for a two-year stint as a foreign correspondent for Vanity Fair, under contract to write two prose pieces a month.

The year she returned to New York, 1923, marked a turning point in her life and career: she received the newly instituted Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and met her future husband Eugen at a house party in Croton-on-Hudson, New York. On their wedding day a few months later, Millay was ill with intestinal problems, so Eugen drove her to Manhattan for emergency surgery immediately following the ceremony. Before the procedure, referring to her Pulitzer Prize, she quipped, “If I die now, at least I’ll be immortal.” 7

Eugen patiently nursed Millay back to health in Croton-on-Hudson and in Greenwich Village, where he rented a narrow three-story brick house at 75½ Bedford Street. From there they embarked on a belated honeymoon, an eight-month trip around the world. When they returned to New York at the end of 1924, Millay answered the New York Times ad that would lead to the next chapter of their lives at Steepletop.

The following spring they moved into the Steepletop farmhouse and replaced the Victorian-style porch with a simpler entranceway that would remind Millay of her home in Maine. “Here we are, in one of the loveliest places in the world, I am sure,” she wrote to her mother and sisters, “working like Trojans, dogs, slaves, etc., having chimneys put in, & plumbing put in, & a garage built, etc. – We are crazy about it – & I have so many things on my mind at the moment that must be done before I’m an hour older, – you know how it is – that I hardly know if I am writing with a pen or with a screwdriver . . .”8

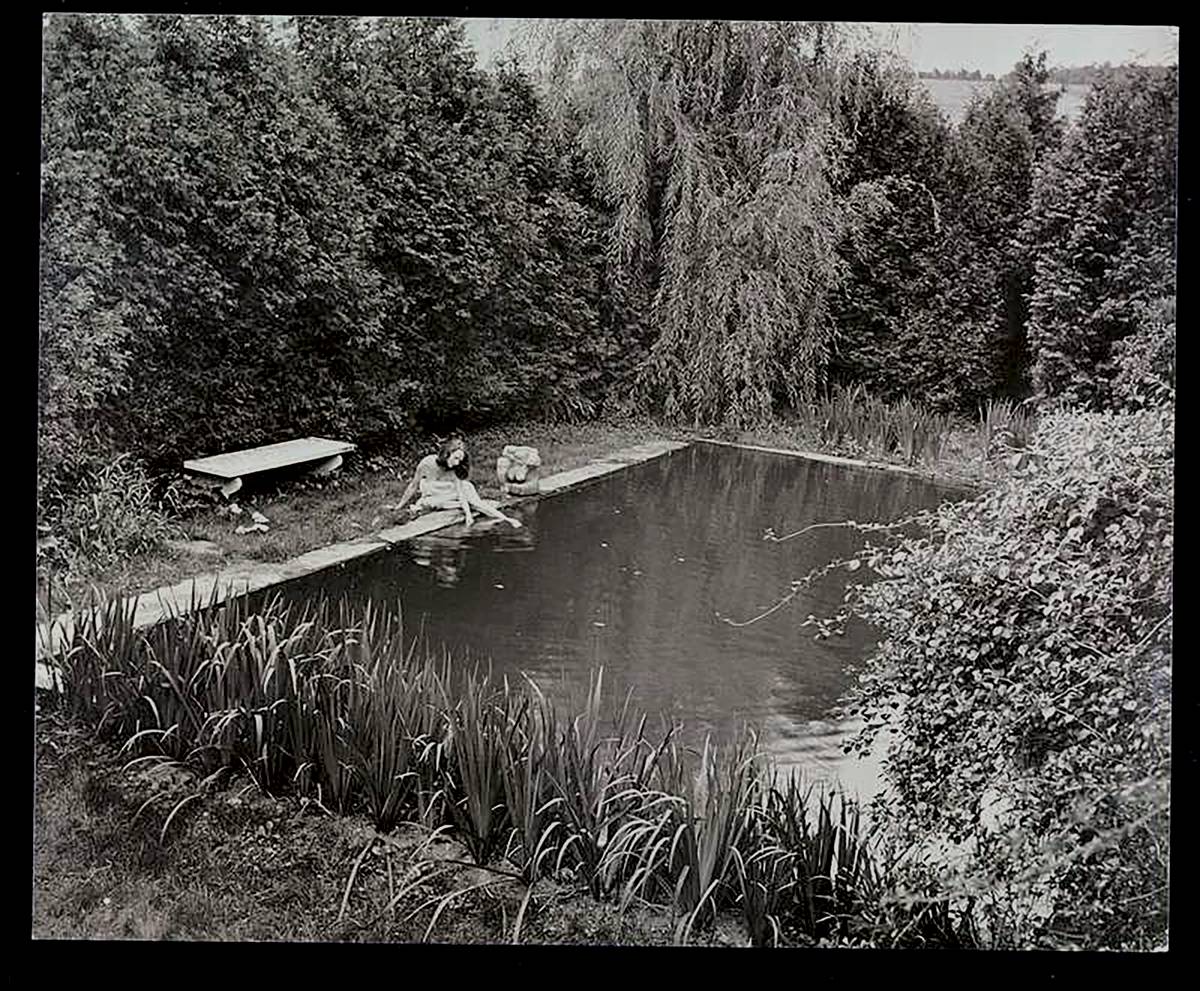

Over the next several years, Millay and Eugen transformed the property into an elegant country estate with flower, herb, and vegetable gardens; guest houses; a tennis court overlooking the Berkshire hills; and a sunken garden area in the foundation of an old barn (“the ruins” ) consisting of seven garden rooms separated by stone walls and arborvitae hedges. The rooms included a bar area complete with stone benches and a fountain, a rose garden, an “iris room,” a spring-fed swimming pool (where they and their guests swam au naturel), outdoor dressing rooms with cast iron dressing tables, and a badminton court in an area called the dingle,9 all accessible through wooden doors hung between trees.

The garden rooms were adorned with art. Norma’s husband, Charlie Ellis, painted a nude that hung over the bar (using automobile paint to withstand the weather) and wooden rondelles that marked the doors leading to the bar, pool, and summerhouse. Eugen also purchased a Sears & Roebuck barn, which went up across the road, for livestock and horses. Millay loved riding and had her own horse and saddle; in later years she developed an affinity for horse racing as well.10

Eugen considered himself a gentleman farmer and set out to recreate a working farm on the property. He hired a handyman, John Pinnie (who would work at Steepletop for decades), and a few other helpers to work the land and plant vegetables to consume and sell. He brought in local children to pick blueberries, and eventually hired other help to pick and crate raspberries, blackberries, strawberries, currants, apples, and pears. He also bought grapes so they could make their own wine, which they stored in racks in the basement. And both he and Millay, who had her own .22 rifle, fished and hunted pheasant and other game birds on the property.

Millay was in her element on the Steepletop hill, surrounded by nature, one of her prime sources for poetic inspiration. With its predictable annual cycles of life and death, growth and decay, nature served as an organizing principle both in her writing and in her life.11 In Fatal Interview, her widely quoted 52-sonnet sequence, the changing seasons mirror the life cycle of a failed love affair. In other poems, her use of seasonal imagery ranges from the traditional, when she equates a pre-winter frost with death (“And you as well must die, beloved dust”), to the unexpected “Oh Autumn! Autumn! –what is the Spring to me?” (from “The Death of Autumn”).

A small outbuilding in a blueberry field was Millay’s first writing cabin, where she was often joined by Altair, her German shepherd. When that structure burned down in 1928, she had another built just up the hill from the house, constructed of unpainted pine boards. In 1931, the year her mother died, she surrounded the cabin with 31 white pines to remind her of Cora and their home in Maine. On the hill leading to the cabin, she planted Narcissus poeticus, also known as the poet’s daffodil. Inside, the furnishings were simple and functional: a small wooden desk and chair, a wood stove, and a chaise lounge.

Steepletop was truly a writer’s sanctuary. There Millay wrote the libretto for an opera set in 10th century England, The King’s Henchman, that would be set to music by one of her close friends, the composer Deems Taylor. When the opera opened at the Metropolitan Opera House in February 1927, there were 17 curtain calls. The New Yorker called it “the greatest American opera so far”12 and more than 10,000 copies of the libretto sold over the next few weeks. Millay was “thrilled to death. That the amounts of royalties I get for a book of poems should be of front page interest to the great new york [sic] public—well, I just sat for ten minutes … drinking it in.”13

Many of her poetry collections were also composed or assembled at Steepletop: The Buck in the Snow (1928); Fatal Interview (1931); Wine from These Grapes (1934); Conversation at Midnight (1936) and the rewrite (after the original manuscript was destroyed in a hotel fire in Florida); Huntsman, What Quarry? (1939); Make Bright the Arrows (1940); a translation of Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal (with George Dillon) that appeared in 1936; and several long poems including The Murder of Lidice (1942) and Poem and Prayer for an Invading Army (1944), commissioned by the Writers War Board.

When she wasn’t writing, Millay spent hours gardening, collecting and pressing hundreds of species of wildflowers, and in true writer fashion, keeping lists of the birds she sighted and detailed notes on her gardening activities: “I must never let the clumps of striped grass get any bigger than they are now ... did all my weeding without a stitch and got a marvelous tan.”14 She and her mother and aunt often exchanged flowers and plants, keeping one another up to date on their progress. Her kitchen garden’s bounty was also news worth sharing with her mothers and sisters:

We had a marvelous garden this summer, and haven’t bought a vegetable for goodness knows how long. Let me tell you, just for fun, what we had from our garden: Potatoes, cabbage, cauliflower, squash, peas, string beans, shell beans, lima beans, cucumbers, radishes, turnips, carrots, pumpkins, sweet corn, tomatoes, eggplants, fennel, parsley, garlic, and CANTALOUPES!15

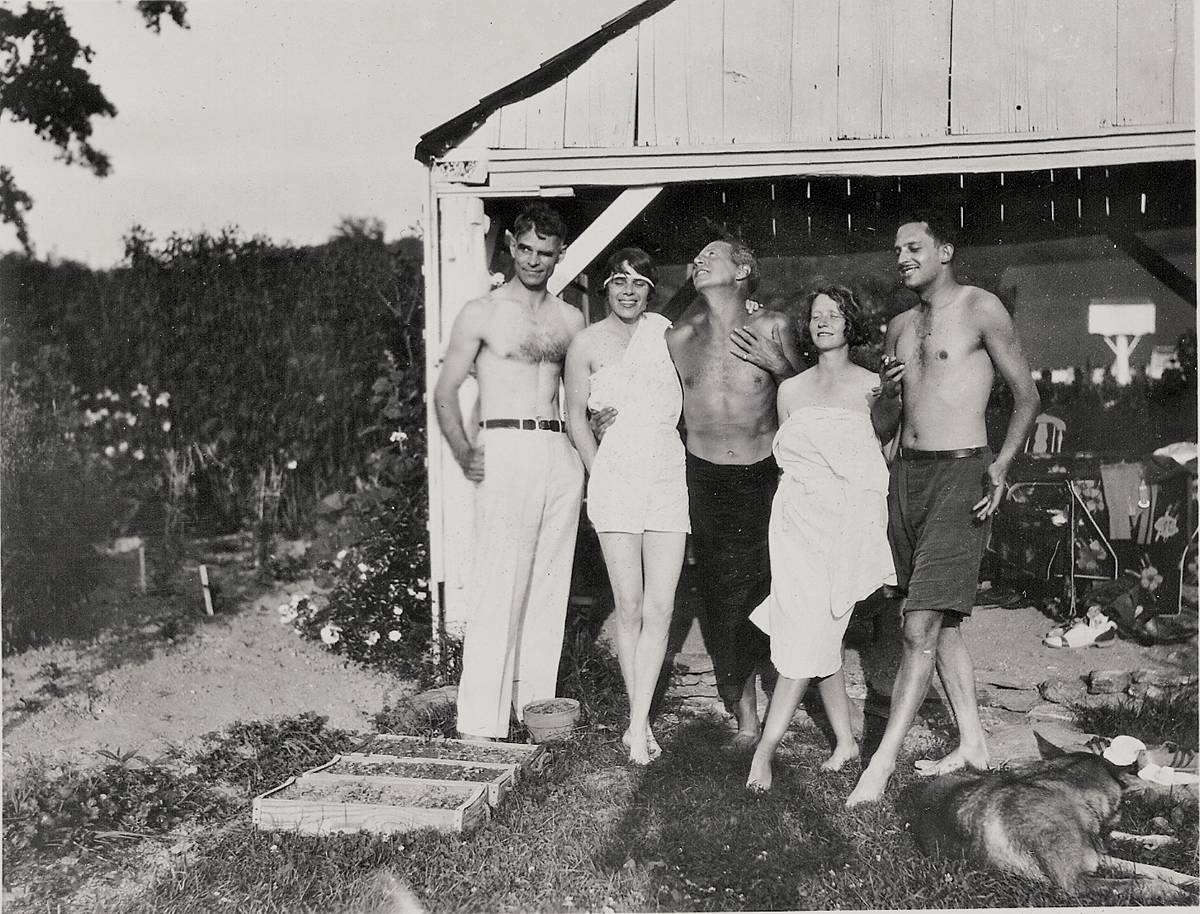

Though Millay suffered from intestinal and other health issues throughout her adult life, she loved to entertain and usually rose to the occasion when visitors arrived. When she was feeling well, she and Eugen hosted parties at the bar, where “the flowers were watered with gin,” and organized elaborate tennis tournaments, complete with prizes and trophies, on a large clay court at the top of the hill. In 1930 they threw a grand three-day house party for 50 or 60 guests who stayed with them and in three of their friends’ homes nearby. The main attraction, besides drinking, swimming in the nude, and other revelry, was a play by a touring group of actors, the Jitney Players, who performed in an amphitheater they constructed on the rise above the house.

Both Millay and Eugen loved the formality of living on a country estate. They brought in household help they called “servants,” usually a couple (at times French or Swedish) who would serve as cook and butler, as well as one or two housekeepers. In the dining room, just a few steps across a stone foyer from the kitchen, Millay had a bell system installed under the dining room table so they could summon the butler during dinner as needed. Following the European tradition, she and Eugen, even when dining alone, dressed up for dinner each night.

When servants were not on site, Eugen prepared meals and tended to other household chores. He had given up his importing business to care for Millay when they moved to Steepletop, believing, he told a journalist, “It is more worthwhile for her to be writing, even if she only writes one sonnet in a year, than for me to be buying coffee for a little and selling it for a trifle more.”16 His self-proclaimed mission in the marriage was to protect Millay from mundane tasks that would distract her from writing poetry, which included handling business details associated with publishing deals and reading tours, as well as running the household.

This living arrangement—with Eugen taking care of everything—suited Millay perfectly. “Eugen and I live like two bachelors,” she said. “He, being the one who throws household things off more easily than I, shoulders that end of our existence, and I have my work to do, which is the writing of poetry.”17

Eugen carried out his domestic duties with good humor and an occasional show of bravado. During their first snowy winter on the hill, when Millay’s mother was staying with them, he wrote to Ficke:

We have 12 tons of coal in the cellar and 15 cords of wood in the shed, three fireplaces, two stoves, a furnace, a hot-water heater and plenty of matches. We have thousands of tins of everything, a huge bag of potatoes, 100 lbs. of sugar, flour, beans, peas, rice... Hanging from the rafters an enormous ham, bacon, pork, a brave brace of ducks, pounds and pounds of coffee, fresh fish frozen into a prehistoric fossil and resuscitated by Mother Millay into glorious New England fish chowder.18

The Steepletop kitchen was a typical New England farm kitchen with a wood-burning cook stove and an “icebox” dependent upon blocks of ice. It was rustic living, as there was no electricity until the late 1940’s when, as Millay described in her poem, “Men Working,” she watched a crew “putting in the poles: bringing the electric light.” Soon afterward, Ladie's Home Journal magazine offered to remodel the kitchen—adding an electric stove, refrigerator, freezer, and porcelain sink—in exchange for full photo coverage and a feature profile of Millay aptly called “Poet’s Kitchen.” Their renovation included painting the walls a fashionable sky blue and adding a breakfast nook with salmon-colored Naugahyde cushions. Millay refused to be photographed for the article, with its well-meaning but unfounded observations about her domestic life. The writer described how the poet “washes dishes and scours pots and pans,” noting “How hard to think of the couplet to close the sonnet when there wasn’t a place to put clean dishes!” And there was more: “And now Miss Millay can wash her woolies in this beautiful kitchen watching the birds!” 19 That line, at least, was accurate: Millay loved watching birds, and in her large living room, called the “withdrawing room,” she often sat at her “bird window” near the brick fireplace and admired the feathered creatures that came looking for food. “She feeds them!” Eugen told a visitor. “She runs a hotel for birds. She’s up and at it every day before dawn.”20

Opposite the bird window were two pianos placed across from one another under the careful gaze of a life-size marble bust of Sappho set on a marble column in the corner. Millay delighted in playing and singing songs she had written, practicing classical pieces she’d learned in early childhood, and inviting other musicians to join her in a duet, trio, or quartet. During the summer she was often joined by the pianist Blanche Bloch21 and her husband, the conductor and composer Alexander Bloch, who ran a music school in Hillsdale, and some of their students. Only music rivalled Millay’s passion for poetry: “Indeed, without music I should wish to die,” she wrote. “Even poetry, Sweet Patron Muse forgive me the words, is not what music is.” 22

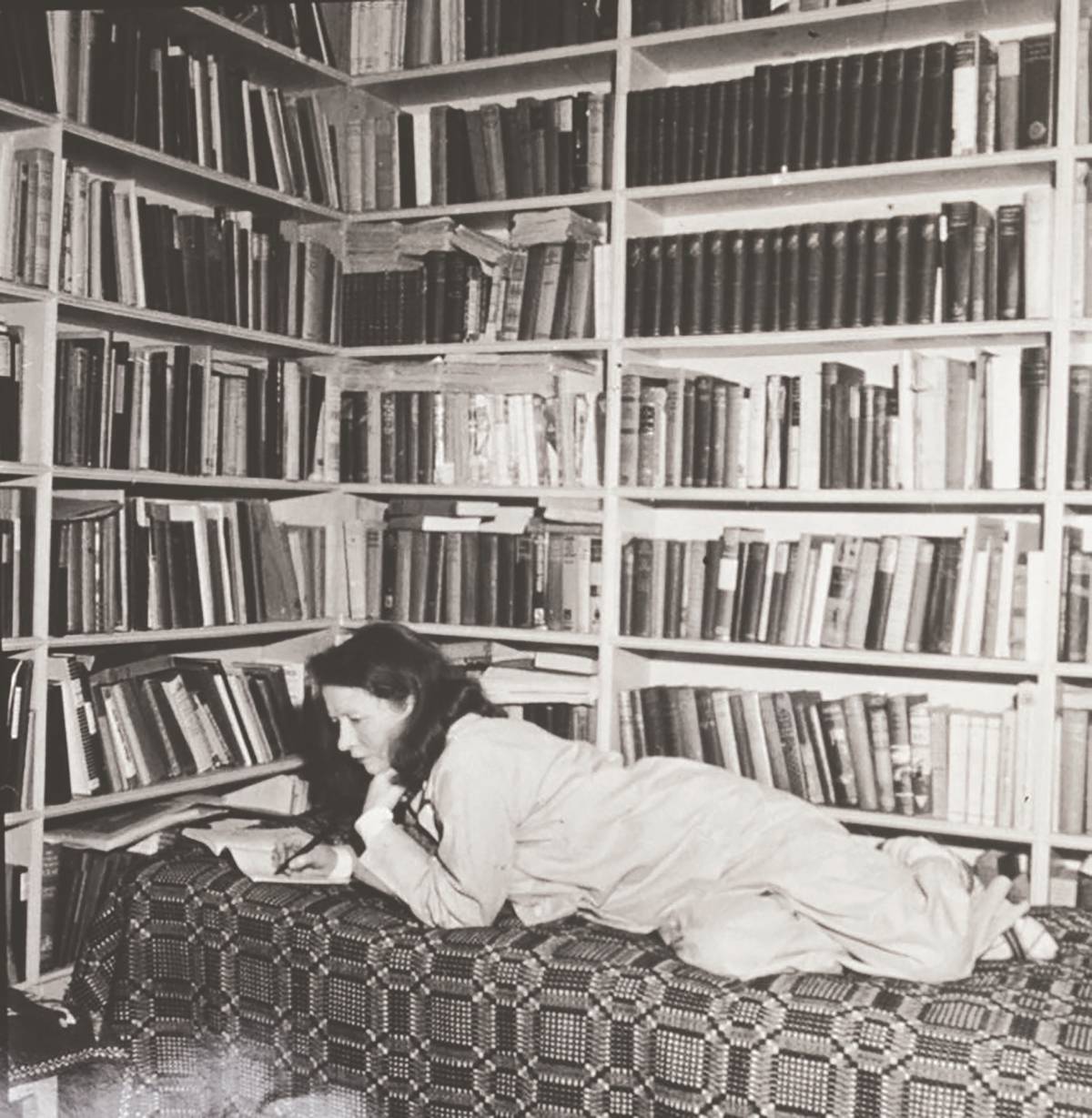

Her most private domain was a small library at the top of the stairs where she wrote and consulted the hundreds of research books assembled there, including a classical encyclopedia and a huge Oxford dictionary mounted on a wooden stand. The walls were lined with poetry collections in English, Italian, French, German, Latin, and Greek, and books of fiction and nonfiction, many personally inscribed by the authors. On the remaining wall space were two sailing charts of Maine’s Penobscot Bay, a pencil sketch of Shelley, a rendering of Sappho, and in later years, a photo of Robinson Jeffers, a poet Millay knew and admired. Above it all, on a rafter in the center of the room, a hand-painted wooden sign demanded “SILENCE” in red block letters.

Her bedroom just around the corner, with its small white brick fireplace, also served as a study of sorts, as Millay often wrote in the mornings in longhand, sitting up in bed, after Eugen had delivered her breakfast on a tray. Some days she would dictate poetry to him to be typed later on. Their mutual love of all things European was reflected in the large bathroom connected to the bedroom, where they had imported and installed a bidet. Another was installed in Eugen’s bathroom down the hall, nearer to his own bedroom and office. Their separate quarters contributed to their shared feeling that their marriage was an open one. In Millay’s words, “I am just as free as when I was a girl,” and in Eugen’s: “Vincent and I live like two men, bachelors, who choose their different jobs. [Yet] we study together. We play together, and it’s a race to keep up with her. It makes me in love with life.” 23

By the late 1930’s, though they remained devoted to one another, their lives began to change as Millay’s health took a downward turn. An accident in 1936, when she had fallen out of a moving car, left her in severe pain that she relieved with alcohol and regular, increasingly addictive doses of morphine. In 1940, as war approached in Europe, she took a strong anti-pacifist stand and published a hastily written book of propaganda poems, Make Bright the Arrows: A 1940’s Notebook, which alienated even her most supportive critics. In the years that followed, the deaths of her sister Kathleen, her beloved editor Gene Saxton, and her dear friend Arthur Ficke sent her to Doctor’s Hospital in Manhattan for treatment of “mental and emotional exhaustion.” But the worst shock was still ahead: in 1949, at age 69, Eugen was diagnosed with lung cancer and died suddenly after surgery in Boston.

Devastated, Millay drank heavily and checked herself into Doctor’s Hospital for treatment of what she called “exhaustion.” But after several days, against the wishes of Norma and her doctors, she decided to return to Steepletop alone to work through her grief. She refused to see visitors and unplugged the phone because she missed hearing Eugen’s voice when he answered a call; he had always picked up on the first ring so it would not disturb her concentration. She relied on the local “postmistress” to pay her bills and answer the hundreds of condolence letters that arrived after Eugen’s death, and depended on her devoted handyman, John Pinnie, to care for the property and bring her mail and groceries and firewood.

She found life without Eugen difficult and lonely, but after several months, she began to fill her notebooks with lines that reflected a gradual acceptance of her loss: “Never before, perhaps, was such a sight! / Only one sky, my breath, and all that blue! / …/ Handsome this day, no matter who has died.”

Clearly Millay’s intention was to rebuild her life and live on her own. Just over a year after Eugen’s death, she was working on a new book of poems and had completed a Thanksgiving poem commissioned by The Saturday Evening Post. But she would never see it published. On October 19, 1950, after staying up all night proofing Latin poetry translations, she slipped and fell down the stairs to her death. She was 58.

Her New York Times obituary reads: “Critics agreed, that Greenwich Village and Vassar, plus a gypsy childhood on the rocky coast of Maine, produced one of the greatest American poets of her time.” 24

The following year Norma and Charlie moved to Steepletop and Norma devoted the rest of her life to preserving and protecting her sister’s legacy. In 1954 she published Mine the Harvest, a collection of unpublished poems and excerpts from Millay’s journals. She also rescued notes and unfinished poems the poet had left in her writing cabin, including these lines:

I hear the rain, it comes down straight;

Now I can sleep, I need not wait

To close the windows anywhere.

Tomorrow it may be, I might

Do things to set the whole world right.

There’s nothing I can do tonight.

A National Historic Landmark, Steepletop is now the home of the Edna St. Vincent Millay Society.25 The Society’s mission is to illuminate Millay’s life and writings and to preserve and interpret the character of her home and gardens, places where nature inspires the creative spirit. Steepletop is open to visitors for house and garden tours and other events in the spring and fall. Though restoration is ongoing, the poet’s furniture and other possessions are on display in the house, and the beautiful gardens and grounds are lined with paths for easy viewing. Visitors can also walk the poetry trail, a wood road leading to the Millay family gravesites. For more information, please see millay.org

Endnotes

1. John Hurd, “Poets and Writers Flock to Bowdoin for the Roundtable of Literature,” Boston Sunday Globe (May 10, 1925), p. 12.

2. Edna St. Vincent Millay: Letters, ed. Allan Ross Macdougall (Camden, ME: Down East Books, 1952), hereafter cited as Letters. Letter to Cora Buzzell Millay (June 22, 1925), p. 95.

3. In Endnote: Letter to “Miss Millay” from Ferdinand Earle (December 3, 1912), Letters, p. 18.

4. Letter to Arthur Davison Ficke and Witter Bynner (December 5, 2012), Letters, p. 20.

5. Deciding between Vassar and Smith, Millay wrote to her mother: “I got a Vassar catalogue from someone today. In Vassar now there are four girls from Persia, two from Syria, two from Japan, one from India, one from Berlin, Germany, and one or two others from “across the water.” The Japanese girls names are Nabe Amagasu and Koto Yamada. Wouldn’t it be great to know them? There isn’t one “furriner” in Smith. Lots of Maine girls go to Smith; very few to Vassar. I’d rather go to Vassar.” Letter to Cora Millay (January 6, 1913), Letters, p. 29.

6. Interview with Vassar President Emeritus Henry Noble MacCracken (November 16, 1966), published in Vassarion, 1967 (Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY).

7. Jean Gould, A Poet and Her Book: A Biography of Edna St. Vincent Millay (Dodd Mead, 1970), p. 159.

8. Letter to Mrs. Cora B. Millay (June 22, 1925), Letters, p. 194.

9. Millay and Eugen placed a marble sculpture of a little Indian boy (circa 1935) by Randolph Rogers in the dingle. Over the years, it has remained a favorite photo subject for professional photographers and other Steepletop visitors.

10. In the 1930’s, Millay used money from poetry royalties to purchase 20 thoroughbreds and a share in a horse farm in Maryland with Bill Brann, a Steepletop neighbor who was good friends with Eugen. For a fascinating account of her short-lived obsession with horse racing, see Daniel Epstein’s What Lips My Lips Have Kissed (Henry Holt & Co., 2001), pp. 248-255.

11. For more on this subject, see “Night is my Sister,” author Holly Peppe’s essay about Millay’s use of nature imagery, in Collected Poems: Edna St. Vincent Millay (Harper Perennial, 2012), PS Section, pp. 2-8.

12. The New Yorker (February 26, 1927), p. 61.

13. 1927 Diary of Edna St. Vincent Millay from the Millay Collection, Library of Congress.

14. Quotes from Millay’s garden diary (May 30th, 1934) from the Millay Collection, Library of Congress.

15. Letter to Mrs. Cora B. Millay (September 24, 1929), Letters, p. 233.

16. Elizabeth Breuer, Interview with Eugen Boissevain and Edna St. Vincent Millay (Pictorial Review, November 1931), hereafter cited as Breuer, Pictorial Review.

17. Breuer, Pictorial Review.

18. Eugen Boissevain, letter to Arthur J. Ficke, Dec. 30, 1925, Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library, Yale University

19. Gladys Taber, Ladies’ Home Journal (February 1949), pp. 56-57, 183,185.

20. Vincent Sheehan, The Indigo Bunting: A Memoir of Edna St. Vincent Millay (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1951), p. 6.

21. See Letter to Mrs. Alexander Bloch (July 13, 1938), Letters, 299.

22. Letter to Allan Ross Macdougall (September 11, 1920), Letters, 101.

23. Breuer, Pictorial Review.

24. “Edna St. V. Millay Found Dead At 58,” Special to the New York Times (October 20, 1950).

25. The Millay Colony for the Arts, founded by Norma in 1973, shares the Steepletop property. A nonprofit residency center for visual artists, writers,